Recount of and poem based on a visit to the Children of the Bomaderry Aboriginal Children’s Home, birthplace of the stolen generation in New South Wales.

Earlier this year, my partner and I decided to visit Bomaderry Children’s Home on our way to Jervis Bay where we had planned a short vacation.

Thousands of people pass the home every day, less than a hundred metres away as they drive by on the Princess Highway, crossing the Shoalhaven River on their way south or north through Nowra, a 200-km drive south of Sydney.

As I turn into the property, I slow down my car intuitively. Something tells me to approach humbly and with respect for this historic place. It’s only later that I discover why this was the right thing to do.

I park our car near the office and we get out. The place is quiet and I cannot see anyone. There are about half a dozen buildings and it feels a little as if they’re raising half an eye to see who has arrived and disturbed their sleep.

But there is life. I make myself known at the office and a helpful Aboriginal woman takes me to another building to meet Nicole, the CEO of Nowra Local Aboriginal Land Council – the organisation which is now looking after the place. While we wait for Nicole, we learn that Uncle Willy is the official library of the Home and it won’t be long before we learn why.

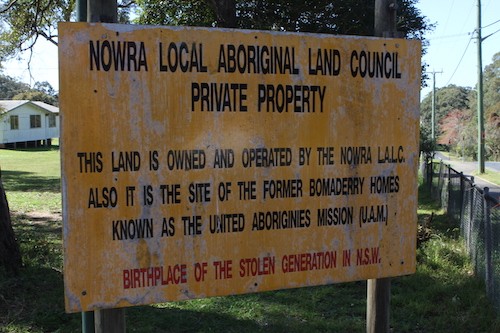

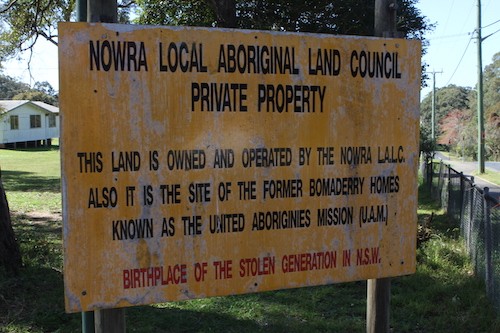

Nicole greets us warmly. She is happy to see curious visitors who are willing to learn and wishes there were more. This place, she says, is the birthplace of a dark chapter of Australian history. The Stolen Generations of NSW started here. The removal of Aboriginal children from their families, a government policy that would haunt not only Aboriginal people, but also Australia as a nation for a long time.

Bomaderry Children’s Home started in 1907 when missionaries took care of a baby girl and a year later looked after six orphaned siblings. In 1909, the NSW government ratified the Aborigines Protection Act and the horrors of forced child removal began.

Bomaderry housed children in dormitories up until the 1960s. Children were not allowed to go home and the missionaries severed them from their culture, language, family, and country. The children were assimilated into white society and when they were old enough, they were sent off to other homes where the boys were trained as labourers and the girls as domestic servants. Many never saw their parents again.

Bomaderry Children’s Home closed in 1988. The NSW Aboriginal Lands Trust bought the property and put it into the care of the local Nowra Aboriginal Land Council.

Nicole is keen to introduce us to the true authority of the place: Uncle Willy Dixon, the caretaker. We meet him outside the cottage where he now lives. His hair has turned white and he maintains a huge grey beard that reminds me of Gandalf from the Lord of the Rings.

Uncle Willy was only four months old when he was taken from his family and forced to live at the Bomaderry Aboriginal Children’s Home. He is a survivor of the stolen generation – and if anyone knows the soul of this place, it is him.

He leaves no doubt about how he cares about Bomaderry. I ask him if I am allowed to take pictures and he permits it for private purposes only, so not for publication. He does not waste time in letting me know what happened to the last person who posted photos online without permission – a young boy and how his mum understood why Uncle Willy smashed his camera. I sense a fierce paternal protection and resilience driving this Elder. I’m sure he looks after this place as if it was one of his children.

Uncle Willy knows every inch here. He points out where walkways have been and buildings once stood. All we can see today is grass, a few remaining concrete plates, and some indentations and raised areas. I try to imagine how life must have been for the children. Too many photographs show them smiling and happy, but if it weren’t forced smiles, it were smiles of innocence and not knowing that the ‘care’ they received was slowly stripping away their Aboriginal identity, layer by layer.

Flowers grow in patches, defiantly, as if to say “We know the history but we grow here regardless”. Do these patches mark places that need particularly healing, I wonder.

Uncle Willy leads us to a special tree. If we could see faces in its bark, he enquires. The bark is wrinkly in places and as I get closer, I can discern round shapes – and yes, there are eyes and mouths – faces! “These are the faces of the children,” explains Uncle. No other tree has these marks. The faces seem to muster me curiously, as children would to find out if you’re a good or bad person. Some seem to have expressions of agony.

At the back of the property is a place Uncle Willy is very proud of because he built it himself. The memorial garden is a place of reflection, a place where visitors can remember and reflect. Native plants grow on the perimeter of a circle that holds a flagpole and a plaque which invites you to honour and respect the children and reminds that the site is the birthplace of the Stolen Generations in NSW. Small yellow footprints lead into the circle, and larger ones lead out at the other end, symbolising the time the stolen children spent here. You can see it on Google Earth where it looks like a portal that could teleport you to another world. Life at Bomaderry certainly was another world for those who passed through.

Some former children are now members of the Children of the Bomaderry Aboriginal Children’s Home (CBACH). Survivors of the Home face many challenges, especially in mental and physical health. The scars are deep, but hope for healing is an eternal flame and high on the agenda of the corporation.

Uncle Willy reminds us to drive out slowly. The path is loosely covered in gravel, and underneath lies the original driveway which is better left undisturbed, he advises. Now I understand my intuitive feeling.

We leave deeply filled with history and a mix of emotions. Sadness and anger for what happened here, but also that so few visitors taken in and learn about this place. Admiration for the people who look after the home, and a sense of angst if all this knowledge will survive into the next generation.

Much later my thoughts form these words:

We were born ready,

Say the children of Bomaderry.

But you replaced our talents and skills

With hard work and other ills.

Gone are we now, but we still yearn

For you to come and seek and learn.

Once you know us you will feel,

And your feelings help us heal.

When our story touches your heart,

We can rest, and you can start.

CBACH is a registered independent charity and accepts donations:

BSB: 062585, Account: 10875665.

Nowra Local Aboriginal Land Council and CBACH have reviewed this text and given their permission to publish.